Review Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Concepts and Prospects of Social Health Insurance in Nigeria

*Corresponding author:Omorogbe Owen Stephen, Edo State Health Insurance Commission, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria.

Received:March 06, 2023; Published:March 23, 2023

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2023.18.002459

Abstract

In the sphere of health, social security is critical for people’s and society’s well-being. It is seen as a fundamental human right, and its implementation helps to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. One of the conceivable organizational systems for obtaining and pooling funds to finance health care is social health insurance. It increases access to health care by reducing catastrophic health expenses and pooling funds to allow cross-subsidization between the wealthy and the poor, as well as between the healthy and the sick. The social health insurance component of Nigeria’s national health insurance program is designed to cover both the formal and informal sectors. Only 5% of the population is covered by the formal sector plan at the moment. Because of its diversity, establishing informal sector plans has been difficult. A survey of relevant literature was used to conduct this study. Using PubMed, Science Direct, Google Scholar, and Google Search, a comprehensive electronic literature search was conducted with search terms that included, but were not limited to, health insurance in Nigeria, social health insurance in Nigeria, health care financing in Nigeria, and public health financing. References cited in pertinent articles and reports led to the discovery of more publications. We only looked at papers that were written in English. There were no date constraints on the searches. On the one side, social health insurance pools people’s health risks, while on the other, contributions from individuals, households, businesses, and the government are pooled. As a result, it protects people against financial and health risks while also being a generally equitable manner of paying health care. Overall, it is critical to maintain and improve a social health insurance system in Nigeria in order to provide inexpensive health care to the entire population. This would significantly cut out-of-pocket spending and improve risk sharing across income categories, age groups, people with varying health statuses, and those living in different geographic areas.

Keywords: Social Health Insurance, Health Insurance in Nigeria, Social Health Insurance in Nigeria, Health Care Financing in Nigeria, and Public Health Financing

Introduction

Universal health coverage is a global goal that all nations, regions, and states have agreed to pursue [1]. Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is defined by the World Health Organization as a manner of arranging, delivering, and financing health services in such a way that “all individuals can get the health care they need without facing financial hardship” [2]. It has two features: first, it covers everyone with a bundle of high-quality essential health services; and second, it provides financial protection from healthcare expenditures, particularly at the time-of-service delivery [2,3]. The goal of safeguarding people from financial problems and social inequalities is embedded in the definition of UHC [1,4].

In recent years, many low and middle-income nations, including Nigeria, have prioritized equal access to highquality healthcare as part of their efforts to achieve universal health coverage (UHC). Financial security, which refers to how much people must spend out of pocket, is a critical component of establishing universal health coverage [4]. There is strong evidence that relying on out-of-pocket payments (OOP) as the primary payment source for healthcare has a negative impact on demand for services, as well as increasing household financial burdens, leading to impoverishment [5-7]. Furthermore, evidence suggests that per capita health spending in many low- and middle-income nations is projected to rise quickly in the long run [8-10,4].

Good health is necessary for economic and social growth, according to a report published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2003. Workers must be healthy in order to work, and children must be healthy in order to go to school and participate in other activities [4]. At the same time, bad health has another serious consequence: it causes poverty since high medical bills can ruin families [2]. A substantial amount of evidence has indicated that healthcare costs are a major source of poverty [11,12]. It has been proven that inadequate prevention and lack of reasonable access to basic health care are the primary causes of poor health in underdeveloped countries [4]. A lack of risk sharing and health insurance causes health-related poverty [2]. Many countries are now searching for a panacea in the shape of formally mandated social health insurance (SHI), which is funded by payroll taxes.

Along with taxation, private health insurance, community insurance, and others, social health insurance (SHI) is one of the available organizational systems for obtaining and pooling funds to support health care [13]. It increases access to health care by reducing catastrophic health expenses and pooling funds to allow cross-subsidization between the wealthy and the poor, as well as between the healthy and the sick [1]. Over time, such schemes have evolved to represent a variety of funding mechanisms, both voluntary and involuntary, with the underlying goal of providing everyone with the option of enrolling in at least one type of mechanism that allows financial risks to be shared [14]. This could include a mix of different sorts of insurance payment for some types of health services, as well as government money for others [1]./

The SHI is aimed to cover both the formal and informal sectors of Nigeria’s national health insurance plan (NHIS). Only 5% of the population is covered by the formal sector plan at the moment [1,14]. The diversity of the informal sector, which includes the urban self-employed, rural community, children under the age of five, permanently disabled persons, prison inmates, tertiary institutions and voluntary participants, and armed forces, police, and other uniformed services, has made setting up informal sector schemes difficult [14,15]. The key difficulty is generating sufficient cash from a diverse collection of people to finance health services without overburdening formal sector workers [1]. This article provides information on the notion of social health finance, which is critical evidence for enhancing financial risk protection for the majority of Nigerians as the country works toward achieving Universal Health Coverage [15]. The research also looks at the differences across main health finance methods in terms of mobilization, resource pooling, and purchasing functions. Finally, it discusses health insurance funding sources in Nigeria.

Methodology

A survey of relevant literature was used to conduct this study. Using PubMed, Science Direct, Google Scholar, and Google Search, a comprehensive electronic literature search was conducted with search terms that included, but were not limited to, health insurance in Nigeria, social health insurance in Nigeria, health care financing in Nigeria, and public health financing in Nigeria. References cited in pertinent articles and reports led to the discovery of more publications. We only looked at papers that were written in English. There were no date constraints on the searches.

The Concept of Social Health Insurance

In the sphere of health, social security is critical for people’s and society’s well-being. It is seen as a fundamental human right, and its implementation helps to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ), social protection in health is a tool for reducing poverty, promoting social and economic development, and smoothing the negative effects of illness on productivity, absenteeism, and the use of private income or savings for health costs [16]. It has been shown that many people in Africa have been unable to pay for medical care in recent decades, with out-of-pocket costs accounting for more than half of overall health spending [16]. In light of this, maintaining and improving a social health insurance system in African countries such as Nigeria is critical in order to provide inexpensive health care to the entire population. This would significantly cut out-of-pocket spending while also enhancing risk sharing among people of various income levels, ages, health statuses, and geographical locations [16,17].

The cultural roots of Social Health Insurance (SHI) can be found in the societies that gave birth to it [18,19]. Germany is frequently credited with inventing this method to health insurance because, in 1883, it was the first western European country to codify existing volunteer organizations into required state-supervised legislation [20]. SHI (Social Health Insurance) is a risk-pooling-based method of financing and managing health care [21]. On the one hand, SHI takes into account people’s health risks, while on the other, it takes into account the contributions of individuals, households, businesses, and the government. As a result, it protects people against financial and health risks while also being a generally equitable manner of paying health care [22,23]. Despite attempts, few least-developed and low-middleincome countries have been able to adequately extend SHI coverage. The majority of countries rely on tax-funded financing, which is also generally equitable [2]. Working people and their employers, as well as the self-employed, typically pay contributions that cover a package of services provided to insures and their dependents in more mature European SHI systems. Most of the time, they are legally obligated to make these donations [13]. Many governments also provide financial support to these systems in order to ensure or improve their long-term viability [13].

There have been a lot of differences in how SHI systems have grown among countries in this environment. Contributions are sometimes pooled into a single fund, or multiple funds compete for membership. These funds may be managed by the government, non-governmental groups, or parastatal organizations [16]. Contributions have generally assured that the wealthy contribute more than the poor, although contributions do not normally vary with health status [13]. SHI systems have progressed as time has passed. Governments, for example, have expanded coverage to persons who are unable to pay, such as the impoverished and jobless, by covering or subsidizing their contributions using government tax or non-tax resources [18]. These days, no SHI system is totally funded by payroll deductions. To account for the fact that it is impossible to exactly identify their wages, the so-called informal sector has been included, often at flat rates (each contributor or family makes the same contribution regardless of wealth) [18]. The differences between systems that people refer to as SHI are so wide these days that even systems that rely on voluntary enrolment are sometimes referred to as SHI [13]. The underlying goal of using the concept appears to be that everyone is offered, or will be offered, the right to enroll in at least one form of mechanism that allows financial risks to be shared over time [13]. This could include a mix of different sorts of insurance payment for some types of health services, as well as government money for others. As a result, the feasibility and long-term viability of any SHI system, generally defined, will be determined by the combination of traits it possesses [13].

Objectives and Guiding Principles Aiming at Establishing a Fair and Sustainable National Health Insurance Scheme

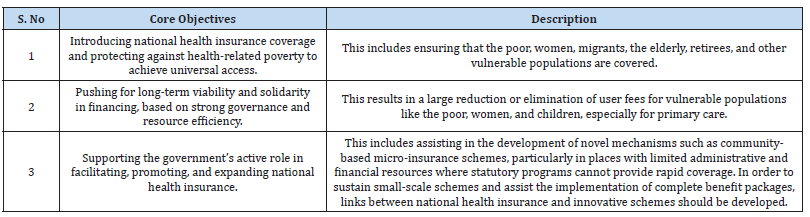

The GTZ, WHO, and ILO Social Health Insurance Consortium has continued to support the government’s efforts to adopt national health insurance around the world [17]. The overarching architecture of national health insurance attempts to improve financial systems in order to contribute to better health, particularly for the poor [16]. As a result, the national health insurance system aims to provide universal access to health services while also coordinating with programs and activities aimed at achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) and poverty reduction measures (PRSP). Efforts to alleviate severe poverty, promote gender equality, remove barriers to women’s access to healthcare, reduce child mortality, enhance maternal health, and combat HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and other diseases are all particularly relevant in this environment [17]. As a result, the national health insurance was created with the following fundamental aims in consideration (Table 1).

Social Health Insurance; The Nigerian Perspective

Every year, 178 million people in developing nations are exposed to catastrophic health costs, with more than 100 million thrown into poverty as a result of these costs [24]. Given the high proportion of out-of-pocket healthcare spending in developing countries, it is reasonable to conclude that health-care costs play a significant influence in population impoverishment and deepening poverty [17]. The poor are frequently burdened financially by illness and the resulting loss of income and savings. Illness frequently leads to a medical poverty trap. In order to cope with the financial burden of ill health, it has been observed that households often use welfare threatening strategies, for example selling assets such as land [21]. From an economic point of view, lack of access to health services affects the competitive capacity of economies in international markets, and from a social point of view, improved access to services and related improved equity are leading to social development and help to promote social peace and stability [16].

In Nigeria and many other Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs), Social Health Insurance Schemes (SHIS) are seen as one of the most important methods for ensuring financial security and Universal Health Care (UHC) for their inhabitants [25,4]. High Out-of-Pocket Expenditure (OOPE) is a major impediment to achieving UHC in Nigeria, where OOPE accounts for more than 70% of total health expenditure, the highest in Africa [4,23]. A variety of health reforms and health finance measures have been implemented in Nigeria in order to minimize the country’s high OOPE. One of these reforms is the National Health Act, which was signed into law in 2014 and includes a key provision of a basic healthcare provision fund comprised of not less than 1% of the federal consolidated revenue fund, which is disbursed to all eligible States in part (about 45 percent of the fund) in addition to the annual budget allocation to health [26]. States have been given rules and standards to follow in order to gain access to these funds, which includes the implementation of state SHIS. This is based on the premise that Social Health Insurance (SHI) will give financial security, reducing catastrophic OOPE while also providing access to basic health services of high quality [4].

SHIS have the potential to effectively help a country move toward UHC by mobilizing additional domestic resources for health through premiums/contributions, implementing critical organizational change for improved health system quality and efficiency, and providing better coverage through increased financial risk protection, particularly for the poor [4]. Contributory health insurance programs, on the other hand, are not wholly new in Nigeria. Due to a variety of issues, including low administrative capacity, small/ fragmented risk pools, and financial sustainability, a National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) and several communitybased health insurance schemes have been implemented with mediocre results, such as extremely low coverage and failed/collapsed schemes [27].

Additionally, Nigeria operates a three-tier federal system of government, each of which is autonomous and has its own executive and legislative branches [15]. Local governments, which make up the third tier of government, have lost a lot of autonomy over the years as state governments have gained more authority over local government administration and funding [28]. Because health is on the concurrent legislative list in Nigeria, both the federal, state, and local governments are responsible for mobilizing and deploying resources for the provision of health services within their respective jurisdictions [15]. Understanding the performance of different health finance mechanisms in Nigeria, as well as the changes that need to be made to their roles to offer better financial risk protection, is critical [15]. It is also valuable to understand the bottlenecks that constrain the implementation of financing mechanisms such as social health insurance that can ensure financial risk protection to most Nigerians. These will help to significantly increase the level of financial risk protection in Nigeria in line with the requirement for achieving UHC [15].

The Nigerian National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS)

The Nigerian National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) was developed in 1999 and officially started in 2005 with the goal of protecting users from financial risk and reducing the enormous burden of Out-of-Pocket Expenditures (OOPs) on individuals and households [29]. The NHIS offers a variety of programs to ensure that no one is left out, including social health insurance for formal sector employees, communitybased health insurance, private health insurance, and voluntary health insurance [30]. The NHIS’ goal of providing all Nigerians with access to high-quality health care has also been considered as a positive step toward achieving universal health coverage (UHC) [30,31]. However, research suggests that the NHIS has failed to accomplish the intended population coverage while also protecting against financial risk [15]. Out-of-pocket expenses account for approximately 90% of total private health spending, putting a substantial financial strain on households, and about 60% of all health spending is paid for directly by households without insurance [32,33]..

Going forward, Health Maintenance Organizations

(HMOs) purchase care on behalf of the National Health

Insurance of USA, and Nigeria adapted the HMO system in

1999 [34]. Private organizations were encouraged to form

HMOs when the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS)

was established [34]. The NHIS Act authorized HMOs to act as

agents for the NHIS, and it should encompass both the public

and private sectors [34]. HMOs were recruited to provide the

Nigerian National Health Insurance Scheme’s (NHIS) Formal

Sector Health Insurance Program (FSSHIP) a private sector

makeover. The scheme’s founders claimed that the country’s

social system was riddled with flaws and lacked checks and

balances [35]. As a result, health policymakers proposed a

health-insurance system in which HMOs act as agents for

the NHIS, purchasing health services from both public and

private providers [29,34]. HMOs are private-sector-driven

organizations that are expected to plug leaks caused by poor

public-sector management [36]. According to Alawode and

Adewole [29], the National Health Insurance Scheme has the

following goals:

a) Ensure that every Nigerian has access to good health

care services.

b) Protect families from the financial hardship of huge

medical bills.

c) Limit the rise in the cost of health care services.

d) Ensure equitable distribution of health care costs

among different income groups.

e) Maintain high standards of health care delivery

services within the Scheme.

f) Ensure efficiency in health care services.

g) Improve and harness private sector participation in

the provision of health care services;

h) Ensure equitable distribution of health facilities

within the Federation.

i) Ensure appropriate patronage of all levels of health

care.

j) Ensure the availability of funds to the health sector

for improved services.

Health Financing Mechanisms in Nigeria

Understanding the current state of health finance in Nigeria, particularly in contrast to national, regional, and global goals and targets, is critical for establishing evidence-based interventions to enhance the financing of healthcare services in the country [34]. Furthermore, because health financing is one of the foundations of the health system, its level of functionality has a direct impact on the health system’s overall performance [37]. The poor functioning of the health financing building block, which is characterized by low public spending, extremely high outof- pocket spending, a high incidence of catastrophic health spending, and impoverishment due to healthcare spending, is a persistent and major weakness of the country’s health system [38,39,37]. A holistic grasp of political, economic, and other institutional elements that either inhibit or promote the implementation of alternative financing mechanisms in different situations in Nigeria is clearly a knowledge deficit in Nigeria [37]. This knowledge will be important in helping Nigeria shape policy and programmatic options that would improve health finance and expedite the country’s progress toward achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) [15]. However, opportunities abound for Nigeria to increase coverage with social health insurance and other financial risk protection mechanisms and ultimately substantially improve the functioning of the health system with healthy citizens [37,40].

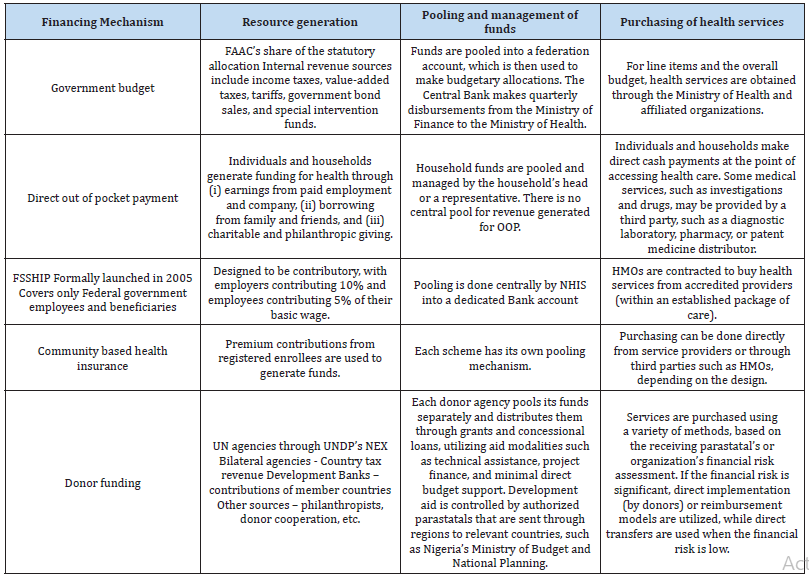

According to Onwujekwe et al. [15], the major health

financing mechanisms in Nigeria are:

(i) government budget using general tax revenue.

(ii) direct out-of-pocket payments;

(iii) a social insurance scheme termed the Formal Sector

Social Health Insurance Programme (FSSHIP) that is

implemented by the National health insurance scheme;

and

(iv) donor funding. Demand-side financing through

conditional cash transfers (CCT) and communitybased

health insurance are two other health funding

approaches (CBHI). Table 2 shows the features of each

health financing mechanism in Nigeria

Social Health Insurance Scheme and its Utilization/Willingness in Nigeria

Across Africa, Asia, and Latin America, a torrent of SHI

initiatives has swept the continent. The World Health

Assembly issued a policy resolution for the World Health

Organization (WHO) in May 2005, stating that SHI would be

used by WHO to mobilize more resources for health, pool

risk, provide more equitable access to health care for the

poor, and deliver better quality health care [17]. The WHO

is pushing its member states to pursue SHI and will provide

technical assistance to those who do so [16]. SHI is being

touted by several international aid agencies, including the

World Bank, the WHO, and the German Agency for Technical

Cooperation, as a policy instrument that could help facilitate

or stimulate four desirable elements of health sector reform

as outlined in the ILO [16] report, namely:

a) When low-income countries lack sufficient tax

revenues to fund health care of a reasonable quality for

all, SHI directs public funds to subsidize premiums for

the poor rather than financing and providing universal

health care for all.

b) Freeing up public funds so they can be directed to

public health goods and services.

c) Shifting public subsidies from the supply side to

the demand side to improve the efficiency and quality

of health care. This distinguishes the responsibilities

for collecting and managing SHI funds from those for

providing health care to patients, with services hired

from distinct corporations. Patients want providers to be

accountable for the services they provide; and

d) Using nongovernmental organizations (NGOs)

and commercial providers’ capacity to improve insured

people’s access to health care through contracting.

SHI may be a solution for a significant aspect of a

country’s systemic health-care problem, but it is not always

a solution for the entire issue [15]. Many developing nations

suffer poor health. In many African countries, the average

infant mortality rate still surpasses 100 per 1,000 live births,

compared to 4 per 1,000 live births in developed economies

[16]. In addition to health-care underfunding, research has

identified at least four other factors that contribute to poor

results in developing countries, including:

a) Poorly targeted public resources disproportionately

benefit the wealthy.

b) Many countries struggle to properly and efficiently

handle their public health systems. To put it another way,

they are unable to convert money into effective and highquality

healthcare.

c) In terms of location and organization, public sector

primary care services do not meet the needs of rural

residents.

d) Health risks are not effectively pooled, resulting in

the exclusion of the poor, low-income, aged, and the less

healthy from insurance.

The National Health Act, which was passed into law in 2014, demonstrated Nigeria’s commitment to lowering OOP and expanding access to excellent fundamental health services (Cambell et al., 2016). The Act defines a legislative foundation for the provision of health services in Nigeria, as well as an organizational and managerial structure [4]. To achieve this important goal of providing quality healthcare to all Nigerians, “the Act specifies that all Nigerians shall be entitled to a Basic Minimum Package of Health Services (BMPHS) to be funded by a basic health care provision fund (BHCPF) derived from contributions of not less than one percent (1%) of the Federal Government’s Consolidated Revenue Fund (CRF) [39]. According to the BHCPF disbursement standards, 50% of the BHCPF is expected to go toward expanding and funding BMPHS, which States could take advantage of by establishing a state contributory health insurance program [4,41]. The BHCPF’s potential and prospects have prompted many Nigerian states (including Kaduna, Lagos, and Delta) to begin planning and implementing a State Social Health Insurance Scheme (SHIS) [42]. As a result of the execution of health reforms in Nigeria, nearly 19 states have signed or are considering signing social health plans into law and implementing them [4,29].

According to studies conducted in other low- and middleincome nations, many people are unaware of the existence of health insurance [43]. Similarly, studies in states in Nigeria have reported low levels of awareness, only (28.9%) in Ilorin, (19.3%) in Lagos and in Abakaliki (25.3%) of the respondents had heard of health insurance before [44-47]. Only (30.1%) had heard of health insurance, and only (2.5%) belong to health insurance scheme in Akwa Ibom State [1]. In respect to willingness to pay for a contributory health insurance scheme, the study of Akwaowo et al. [1] in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria, revealed that majority of respondents (82%) were willing to pay (WTP) for a contributory health insurance scheme. Other studies carried out in states in Nigeria have also reported high levels of WTP with (87%) in Osun, (82%) in Kaduna, (89.7%) in Port Harcourt [4,44- 46]. Similar findings has also been reported in other LMICs like Sierra Leone and Ethiopia. Indicating that rural dwellers are willing to pay for a contributory health insurance scheme [43,48]. Therefore, further sensitization is required for a proper utilization of social health insurance benefits.

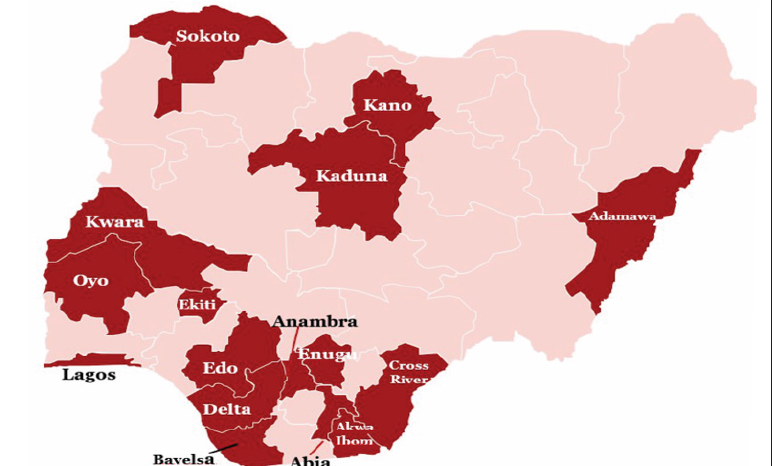

States in Nigeria that have Commenced the Establishment of State Health Insurance Schemes

In order to improve access to high-quality healthcare, the World Health Assembly in 2005 urged governments to prioritize Universal Health Coverage (UHC). This is still a feasible option for providing suitable preventive, curative, and rehabilitative services to the general public at a reasonable cost [17]. As a result, global stakeholders have placed a high value on health-system funding structures [22,6]. Apart from the tax-based (Beveridge model) way of health funding, Social Health Insurance (SHI) (Bismark model), which originated in Germany in the nineteenth century, is one of many approaches used to address the issues of providing access to health care services for the poor [29]. Healthcare finance is crucial to the growth of a country’s health system, necessitating the implementation of long-term health financing frameworks as well as tracking progress toward UHC [29]. Nigeria’s healthcare system is currently undergoing massive reforms in health-care financing in order to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC) [1]. Nigeria’s federal government has indicated that all states establish and operate required state health insurance plans [49]. To this purpose, numerous states across the country have implemented statewide health insurance plans [50]. The National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) now has the mandate to protect all Nigerians from paying for healthcare out of pocket, pursuant to the passing of the health insurance bill. However, in order to attain UHC in Nigeria, a functioning NHIS that follows the bill’s directives is required [1]. Several states have begun the process of establishing State Health Insurance Schemes to fill the coverage gap. As illustrated in (Figure 1), a total of sixteen states are currently in various phases of implementation [1]. These plans usually entail the creation of a governing body to monitor the scheme’s implementation and management [1]. They have also created benefit packages to cover the most frequent medical issues. State governments, on the other hand, have agreed to provide a portion of their consolidated revenue to the plan in order to cover premiums for the state’s poor and vulnerable residents [1].

Results

In Africa, the challenge of universal health coverage is

crucial, particularly in terms of assuring financial security

and access to necessary health care for individuals who do

not work in the formal sector [29]. A fundamental barrier

to health care finance in Nigeria is the high degree of outof-

pocket spending and the lack of insurance mechanisms to

pool and manage risk [29,51]. In 2006, the Federal Ministry

of Health issued the National Health Financing Policy [14].

Through the development of a fair and sustainable finance

structure, the policy aims to promote equity and access to

high-quality, affordable health care, as well as ensure a high

level of efficiency and accountability in the system [14]. The

revenue mobilization and pooling strategies to increase the

fiscal space while ensuring fair financing, including risk

protection of the vulnerable financing include:

a) Requiring federal, state, and local governments to

dedicate 15% of their total expenditures to health, as

stated in the Abuja Declaration of 2000.

b) Creating SHI and CBHI schemes under the NHIS

in order to increase coverage to the informal and rural

populations, which account for 70% of the population, as

part of a goal to achieve universal access.

c) Assistance to states in developing state-run health

insurance plans that will be regulated by the NHIS.

d) Discouragement of retainership and support for

voluntary (private) health insurance

e) Identifying, adopting, and scaling up financing

schemes that have been proved to accelerate universal

coverage, such as drug revolving fund systems, deferrals,

and exclusions, among others.

f) Harmonization of external aid and health-financing

partnerships

g) Promotion of domestic philanthropy

The term “health insurance” refers to the pooling of health risks in order for members to get benefits owing to the uncertainty surrounding the occurrence of illness and costs for treating that illness [52]. The beneficiaries of the National Health Insurance Program are supposed to pay 15% of their monthly salaries to the scheme, with the federal government covering 10% and the beneficiary covering the remaining 5% [14]. The 15 percent basic salary payroll deduction has not been achieved, and the majority of the formal sector (federal, state, local government, and organized private sector) has yet to sign up for the scheme. State buy-in is still minimal, although some private enterprises offer health insurance to their employees, covering roughly 1% of Nigerians [14,19]. The NHIS continues to provide a small contribution to health funds, accounting for around 2% of total health spending, and it is hampered by low penetration, low acceptance, and limited benefit packages [23]. The most common source of healthcare funding is OOP from households, which accounts for 69 percent of all healthcare spending, followed by government funding, which is allocated from the federation account’s general revenue to the various levels of government based on an agreed revenue allocation formula [14].

Conclusions

Given the existing state of main health financing mechanisms in Nigeria, it has been noticed that service quality is subpar, and individuals and families are not shielded against catastrophic health costs. However, through the National Health Act, which was signed into law in 2014, Nigeria has demonstrated some commitment to lowering out-of-pocket spending, which accounts for a larger share of total private health spending and expanding access to excellent basic health care. Overall, the findings of this study show that, in order to improve health finance in Nigeria, the government must dramatically raise the health budget. Advocacy for greater money, as well as resultand evidence-driven finance, should include key decision makers. Amendments to the legislation that established the national health insurance program, which made health insurance voluntary rather than mandated, are among the necessary modifications in social health insurance. Coverage of the informal sector should be expanded, and appropriate advocacy mechanisms should be developed.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflict of Interest

The Authors declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Akwaowo CD, Umoh I, Motilewa O, Akpan B, Umoh E, et al. (2021) Willingness to Pay for a Contributory Social Health Insurance Scheme: A Survey of Rural Residents in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Front. Public Health 9: 654362.

- (2003) World Health Organization Social Health Insurance. Report of a Regional Expert Group Meeting New Delhi, India, 13-15 March 2003. World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia. New Delhi. June 2003.

- Okpani AI, Abimbola S (2015) Operationalizing universal health coverage in Nigeria through social health insurance. Niger Med J 56(5): 305-310.

- Ogundeji YK, Ohiri K, Agidani AA (2019) Checklist for designing health insurance programmes – a proposed guidelines for Nigerian states. Health Res Policy Sys 17(1): 81-91.

- Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, et al. (2003) Understanding household catastrophic health expenditures: A multi-country analysis. Lancet 362: 111-7: 565-572.

- McIntyre D, Garshong B, Mtei G, Meheus F, Thiede M, et al. (2008) Explaining the incidence of catastrophic expenditures on health care: Comparative evidence from Asia. Bull World Health Organ 86: 871-876.

- Onwujekwe O, Velenyi E (2006) Feasibility of Voluntary Health Insurance in Nigeria. Washingt DC World Bank.

- Rancic N, Jakovljevic M (2016) Long Term Health Spending Alongside Population Aging in N-11 Emerging Nations. East Eur Bus Econ J 2: 2-26.

- Jakovljevic M, Groot W, Souliotis K (2016) Health Care Financing and Affordability in the Emerging Global Markets. Front Public Heal 21: 4-2.

- Jakovljevic M, Potapchik E, Popovich L, Barik D, Getzen TE, et al. (2017) Evolving Health Expenditure Landscape of the BRICS Nations and Projections to 2025. Heal Econ (United Kingdom) 26(7): 844-852.

- Basaza RK, O Connell TS, Chapčáková I (2013) Players and processes behind the national health insurance scheme: a case study of Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res 13: 357

- Nosratnejad S, Rashidian A, Dror DM (2016) Systematic review of willingness to pay for health insurance in low and middle income countries. PLoS ONE 11: e0157470.

- Doetinchem O, Carrin G, Evans D (2010) Thinking of introducing social health insurance? Ten questions. World Health Report: 26.

- Uzochukwu BSC, Ughasoro MD, Etiaba E, Okwuosa C, Envuladu E, et al. (2015) Health care financing in Nigeria: implications for achieving universal health coverage. Niger J Clin Pract 18(4): 437-444.

- Onwujekwe O, Nkoli E, Chinyere M, Felix O, Hyacinth I et al. (2019) Exploring effectiveness of different health financing mechanisms in Nigeria; what needs to change and how can it happen? BMC Health Services Research 19: 661.

- (2021) ILO, WHO and GTZ Social Health Insurance: Solidarity is the Key.

- WHO (2005) Towards a national health insurance system in Yemen – Part 1: Background and assessments. 75-83.

- Gina Lagomarsino, Alice Garabrant, Atikah Adyas, Richard Muga, Nathaniel Otoo (2012) Moving towards universal health coverage: health insurance reforms in nine developing countries in Africa and Asia. Lancet 380: 933-943.

- Owumi B, Adeoti A, Patricia AT (2013) National Health Insurance Scheme dispensing outreach and maintenance of health status in Oyo State. Int J Humanit Soc Sci Invent 2(5): 37-46.

- Saltman RB (2004) Social health insurance in perspective: The challenge of sustaining stability. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Serie.

- Ezat W, Puteh S, Almualm Y (2017) Catastrophic health expenditure among developing countries. Health Syst Policy Res 4: 1-7.

- (2015) World Health Organization World Bank. Tracking universal health coverage: first global monitoring report.

- Adewole DA, Adebayo AM, Udeh EI, Shaahu VN, Dairo MD, et al. (2015) Payment for health care and perception of the national health insurance scheme in a rural area in Southwest Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg 93(3): 648-654.

- Ama P, Fenny RY, Rachel T (2021) Strategies for financing social health insurance schemes for providing universal health care: a comparative analysis of five countries. Glob Health Action 14: 1.

- Obermann K, Jowett M, Kwon S (2018) The role of national health insurance for achieving UHC in the Philippines: a mixed methods analysis. Glob Health Action 11(1): 1483638.

- Aregbeshola BS, Khan SM (2018) Out-of-pocket payments, catastrophic health expenditure and poverty among households in Nigeria 2010. Int J Health Policy Manag 7(9): 798-806.

- Osamuyimen A, Ranthamane R, Qifei W (2017) Analysis of Nigeria Health Insurance Scheme: Lessons from China, Germany and United Kingdom. IOSR J Humanit Soc Sci 22(4): 33-39.

- Okafor J (2010) Local government financial autonomy in Nigeria: the state joint local government account. Commonwealth J Local Gov (6): 127-131.

- Alawode GO, Adewole DA (2021) Assessment of the design and implementation challenges of the National Health Insurance Scheme in Nigeria: a qualitative study among sub-national level actors, healthcare and insurance providers. BMC Public Health 21(1): 124.

- Onwujekwe O, Onoka C, Uzochukwu B, Hanson K (2011) Constraints to universal coverage: Inequities in health service use and expenditures for different health conditions and providers. Int J Equity Health 10(1): 50.

- Thomas S, Gilson L (2004) Actor management in the development of health financing reform: health insurance in South Africa, 1994–1999. Health Policy Plan 19(5): 279-291.

- Ibe O, Honda A, Etiaba E, Ezumah N, Hanson K, et al. (2017) Do beneficiaries’ views matter in health care purchasing decisions? Experiences from the Nigerian tax-funded health system and the formal sector social health insurance program of the national health insurance scheme. Int J Equity Health 16(1): 216.

- Asante A, Price J, Hayen A, Jan S, Wiseman V (2016) Equity in health care financing in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of evidence from studies using benefit and financing incidence analyses. PLoS One 11(4): e0152866.

- Obikeze E, Onwujekwe O (2020) The roles of health maintenance organizations in the implementation of a social health insurance scheme in Enugu, Southeast Nigeria: a mixed-method investigation. Int J Equity Health 19(1): 33.

- Chima OA, Kara H, Johanna H (2015) Towards universal coverage: a policy analysis of the development of the National Health Insurance Scheme in Nigeria. Health Policy Plan 30(9): 1105-1117.

- Njau RJA, Mosha FW, De Savigny D (2009) Case studies in public-private partnership in health with the focus of enhancing the accessibility of health interventions. Tanzan J Health Res 11(4): 235-249.

- Onwujekwe OE, Onoka CA, Nwakoby IC, Ichoku HE, Uzochukwu BC, et al. (2018) Examining the financial feasibility of using a new special health fund to provide universal coverage for a basic Maternal and Child Health benefit package in Nigeria. Front Public Health 6: 200.

- World Health Organization and World Bank Group (2014) Monitoring progress towards universal health coverage at country and global levels. Framework measures and targets. Geneva: World Health Organization and World Bank.

- Federal Ministry of Health (2016) Guidelines for the Administration, Disbursement, Monitoring and Fund Management of the basic Healthcare Provision Fund.

- Chang A, Cowling K, Micah AE (2019) Past, present, and future of global health financing: a review of development assistance, government, out-of-pocket, and other private spending on health for 195 countries, 1995-2050. Lancet 393(10187): 2233-2260.

- Campbell P, Owoka O, Odugbemi T (2016) National health insurance scheme: are the artisans benefitting in Lagos state, Nigeria. J Clin Sci 13(3): 122-131.

- Babatunde O, Akande T (2012) Willingness to Pay for Community Health Insurance and its Determinants among Household Heads in Rural Communities in North-Central Nigeria. IRSSH 2: 133-142.

- Agago TA, Woldie M, Ololo S (2014) Willingness to join and pay for the newly proposed social health insurance among teachers in Wolaita Sodo Town, South Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 24(3): 195-202.

- Azuogu BN, Eze NC (2018) Awareness and willingness to participate in community-based health insurance among artisans in Abakaliki, Southeast Nigeria. Asian J Res Med Pharm Sci 4(3): 1-8.

- Bamidele JO, Adebimpe WO (2012) Awareness, attitude and willingness of artisans in Osun State Southwestern Nigeria to participate in community-based health insurance. J Community Med Prim Health Care 24(1-2): 1-10.

- Anderson IE, Adeniji FO (2019) Willingness to pay for social health insurance by the self-employed in Port Harcourt, Rivers State; A Contingent Valuation Approach. Asian J Adv Res Rep 7(3): 1-15.

- Abiola AO, Ladi Akinyemi TW, Oyeleye OA, Oyeleke GK, Olowoselu OI, et al. (2019) Knowledge and utilisation of National Health Insurance Scheme among adult patients attending a tertiary health facility in Lagos State, South-Western Nigeria. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 11(1): e1-e7.

- Dong H, Kouyate B, Cairns J, Mugisha F, Sauerborn R (2003) Willingness-to-pay for community-based insurance in Burkina Faso. Health Econ 12(10): 849-862.

- Ojerinde D (2019) Make Health Insurance Mandatory, Clearline HMO Tells Federal Government. Punch Newspapers.

- Oladimeji Akeem Bolarinwa, Munirat Ayoola Afolayan, Bosede Folashade Rotimi, Bilqis Alatishe Mohammad (2021) Are There Evidence to Support the Informal Sector’s Willingness to Participate and Pay for Statewide Health Insurance Scheme in Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J 28(1): 71-73.

- Ezeoke OP, Onwujekwe OE, Uzochukwu BS (2012) Towards universal coverage: examining costs of illness, payment, and coping strategies to different population groups in southeast Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg 86(1): 52-57.

- Onwujekwe O, Okereke E, Onoka C, Uzochukwu B, Kirigia J, et al. (2010) Willingness to pay for community based health insurance in Nigeria: Do economic status and place of residence matter? Health Pol Plan 25(2): 155-161.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.